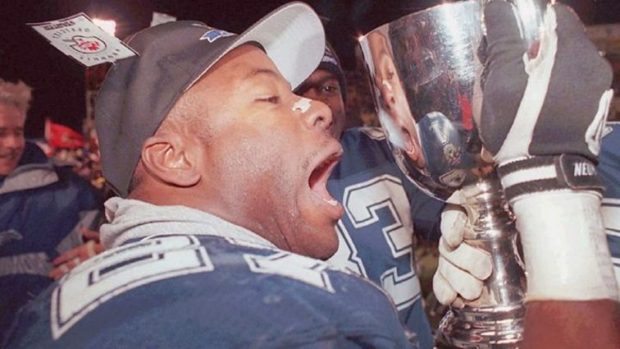

Mike Pringle holds the Grey Cup in Regina, Canada on November 19th, 1995 Tom Hanson/AP

Twenty years ago, a group of American players won the Grey Cup, broke the heart of a nation and helped bring the NFL back to Baltimore

On November 19, 1995, more than 52,000 people trudged into Taylor Field in Regina, Saskatchewan, to witness what would become the most pivotal game in the history of the Canadian Football League. It was the day of the 83rd Grey Cup, so named for the silver trophy bestowed upon the CFL’s annual champion.

The weather was very Canadian, with temperatures dipping below zero and winds gusting to around 50 mph. The crowd, though, was spirited, ready for anything and decidedly on the side of the Calgary Stampeders, led by superstar quarterback Doug Flutie. The former Boston College star had been named the CFL’s Most Outstanding Player for four years running, but 1995 was arguably his most incredible season yet. Surgery in August on a torn tendon in his throwing elbow was supposed to keep him out eight months, but he returned in time for Calgary’s regular-season finale and led them through the playoffs and to the championship game. With backup quarterback Jeff Garcia keeping the team afloat and competitive in Flutie’s absence, Calgary had gone 15-3, tied with their Grey Cup opponent for the best record in the league.

That team was the Baltimore Stallions, a franchise in only its second year of existence. (The Stampeders date back to 1935, older than all but eight NFL teams.) Under the guidance of CFL Commissioner Larry Smith – himself a former CFL player for nine seasons in Montreal – Canadian football officially entered the American market in 1993 with the Sacramento Gold Miners, excavated from the remains of the Sacramento Surge of the defunct World League of American Football. In 1994, the CFL added franchises in Las Vegas; Shreveport, Louisiana; and Baltimore. But in 1995, Smith orchestrated a radical expansion project that essentially split the CFL conferences into direct, opposing entities: the North Division with eight Canadian teams and the South Division with five American teams. CFL franchises were awarded to Memphis and Birmingham, Alabama, and the Sacramento team moved to San Antonio to play in the Alamodome as the newly christened Texans.

It was a risky power play for a league whose future was seen as somewhat tenuous, but Smith put on a brave face in public.

“I think we’ve positioned ourselves to protect ourselves,” he told TSN in an interview before the 1995 season. “Let’s face it: The NFL is very strong. We’re selling a unique product. We’re creating our own niche. We don’t compete against the National Football League. We have to compete against ourselves.”

And now, a controversial season had come down to one night in Regina. With a longer and richer history than its American counterpart, the CFL has an importance to Canadians that can’t possibly be overstated. It’s football but a slightly different blend. There are 12 players aside (not 11). You get three downs to gain ten yards (not four). The field is longer and wider, the goalposts are positioned differently, the scoring is slightly more inventive, and the game ends not with zeros on the clock but with a final play. The Stallions had already learned about this last difference all too painfully. As a nameless team adorned with a horsehead on its helmet – the NFL sued to keep them from dubbing themselves the “Colts” – the Baltimore team made it all the way to the 1994 Grey Cup and lost to the B.C. Lions, 26-23, on a field goal with no time remaining. They left the Lions’ home stadium in Vancouver disappointed but determined to return.

On the sidelines during that game was Carlos Huerta, who had been named the CFL’s West Division Rookie of the Year as a kicker for the Las Vegas Posse. Huerta was a native of South Florida, was an All-American at Miami and won a national championship with the Hurricanes in 1991. Going from The U to the uppermost reaches of professional football was an easy-enough transition for Huerta, who watched in awe as B.C.’s Lui Passaglia punched through a 38-yard kick to win the Grey Cup. As the Lions players stormed the turf in celebration, Huerta turned to his girlfriend Christine (now his wife) and smiled.

“I was born to make that kick,” he said.

In an effort to sell Canadian football to American fans, the CFL printed up thousands of promotional booklets in 1995 titled FIRST & TEN FROM THE FIFTY-FIVE: CANADIAN FOOTBALL EXPLAINED. It’s 21 pages full of everything a newbie fan would need to know: the in-game differences, both obvious and subtle; information on every franchise, both home and abroad; and histories of the league and the Grey Cup. As the media relations director for the Sacramento/San Antonio franchise, Tim McDowd lived this crash course in CFL football, as did many of his stateside colleagues.

“It’s still football at the end of the day, and I think that that’s what we learned: focus on the football, focus on trying to get the community to know the players, let the players become the face of the franchise,” he says. “We fought this perception that the CFL was minor league, that it’s the second tier.”

Still, despite all that preparation, McDowd concedes that “teaching Canadian football league rules to Texas football fans was an uphill battle.”

It doesn’t help that the pamphlet stresses words like “product” and “brand,” like the result of some overeager marketing executive, but the gist of the pocket guide is to convey the sense that not only are American and Canadian football not that dissimilar, but that it’s those differences that give the CFL a more exciting sport with higher scoring and unique rhythms – “a fast-paced, sizzling brand of football which is taking North America by storm,” as it reads.

On the back of that program is a motion-blurred shot of Mike Pringle, perhaps the greatest running back in the history of the CFL. At 5-foot-9 and out of Cal State Fullerton, Pringle was cut by the Atlanta Falcons during the 1991 preseason and signed with the CFL’s Edmonton Eskimos, but they released him after three unimpressive games. He spent the rest of 1992 with the World League’s Sacramento Surge, a team most notable for featuring defensive tackle/future wrestling star Bill Goldberg. When they folded, Pringle followed the franchise to the CFL and played one season for the newly minted Gold Miners, gaining 366 yards before signing with the Baltimore franchise before the 1994 season.

The rest is Canadian football history. Pringle rushed for a league-record 1,972 yards, a mark that stood until he broke it in 1998 and became the first (and still only) CFL player to eclipse 2,000 rushing yards in a season. Playing under legendary coach Don Matthews, Pringle became a nimble and bruising back, with a long stride that gained every inch humanly allotted to his gait. He was more Walter Payton than Emmitt Smith – still the only two professional football players to surpass his career mark of 16,425 rushing yards. In a league that was almost entirely dictated by passing, Pringle redefined the very idea of a CFL running back. Flutie won the Most Outstanding Player Award that year, but Pringle had become a bona fide star.

Even though it ended in heartbreak, the 1994 season was more than Pringle and the rest of the Stallions could have ever expected. Baltimore was a city that had football ripped from his heart in the predawn hours of March 29, 1984, when, under cover of darkness and deceit, Colts owner Robert Irsay quietly moved the Colts to Indianapolis. For more than 10 years, Baltimore was without pro football, and then a Virginia businessman named Jim Speros invested millions of his money to not only bring a franchise to Baltimore but to also renovate old Memorial Stadium.

With the 1994 baseball strike underway, the Baltimore CFLs, as they were known, were the only major professional sports team playing in the city at that time. Not only did Speros use that to his advantage in promoting the team, he reaped the benefits of ad dollars that were no longer earmarked for the Orioles and had to go somewhere.

“You never like to benefit from someone else’s misfortunes,” CFL commissioner Larry Smith said at the time, “[but] the strike is not going to do anything but help us.”

And Baltimore rewarded its fans with a surprise run to the Grey Cup, and that was a wakeup call to Canadian fans. Much in the same way that NFL rosters are often very American, CFL rosters are actually very Canadian. There’s this perception that it’s all just NCAA cast-offs and players who maybe can’t cut it in the NFL. But the reality is that these rosters are consciously Canadian, stocked with players who were born in Canada and played their college ball there. The 1995 Stallions, on the other hand, did not have a single Canadian on their roster. Smith had willfully constructed the league as United States vs. Canada, and the Stallions were the living embodiment of that ideal.

No matter their collective nationality, the Stallions were a football force that could not be stopped. They won 15 games and the roster was stocked with talent on both sides of the ball. With Pringle at running back, fellow future CFL Hall of Famer Tracy Ham at quarterback, and an offensive line that dominated at will, the offense was quick and explosive when needed. The defense, led by 18 sacks from future Hall of Fame defensive tackle Elfrid Payton (whose son is the starting point guard for the Orlando Magic), the Stallions gave up the third-fewest points in the league. On special teams, Carlos Huerta was dominant. His 57 field goals that season are still the second-most in CFL history, and in the semifinal game against the San Antonio Texans, Huerta nailed seven field goals in a 21-11 win. (He still has the gold Bulova watch he got for earning Player of the Game honors that day.) Baltimore had wanted to make him the highest-paid kicker in CFL history before the season, but Huerta chose to play out his option year in the hopes of a bigger eventual payday or even a legit shot at a starting NFL job.

A notable performance in the 1995 Grey Cup would all but assure that gamble paid off.

As a media relations director for the Toronto Argonauts, Mike Cosentino was also on the sidelines during the 1994 Grey Cup, like Huerta and many others. Even though the Argos hadn’t qualified for the championship game, all the team P.R. directors show up to work the event, which means Cosentino was among some 55,000 fellow Canadians, holding his breath that B.C. could somehow pull off the win and keep the Grey Cup within its home borders.

“It was going to be an unbelievable, ‘are-you-kidding-me?’ moment,” Cosentino says. “There was a big sigh of relief that it didn’t happen, honestly.”

But soon enough it became clear that Baltimore was back for more in ’95, that the Stallions were the class of the CFL and had a legit chance of winning it all. And among all the American CFL franchises, the Stallions were regarded internally as the only one pulling its weight at the turnstiles. As they kept winning, the fans kept showing up. The Stallions had fewer than 27,000 in attendance in a home game only once that season and typically hovered around 30,000. By the time Baltimore finished its regular season 15-3, the rumors that Art Modell was thinking of relocating the Cleveland Browns were full-blown.

Finally, on November 6, 1995, two days after the Stallions defeated the Winnipeg Blue Bombers, 36-21, in the first round of the CFL playoffs, the news was made official. The Browns were moving to Baltimore for the 1996 season, which meant the Stallions – by virtue of their own popularity, which proved that professional football in the city was a viable enterprise – were effectively gone. In the New York Times’ 1,200-word story about Modell the next day, the Stallions were not mentioned even once.

“When we found out it was a fait accompli,” Pringle says, “I took the Browns’ roster and I wrote their names on tape and put them over everybody’s nameplate in the locker room – except mine.”

Pringle’s motivating maneuver added some levity to a stressful situation, but Huerta’s seven field goals in the South Division final ensured that Baltimore would survive to play one final game in franchise history – in Regina for the Grey Cup.

The start of the game was delayed on account of the unyielding winds, and there was doubt that temporary seating at one end of the stadium would even stay up in such conditions. There was snow on the sidelines but the sky was clear and the wind biting. The Stallions had practiced that week in Regina so the weather was not a shock to their system. In fact, they planned to use the elements to their advantage by running the ball, milking the clock, and tiring the Calgary defense.

“We were going to stay on the field offensively as long as we could – and keep Doug on the sideline,” Pringle says. “The best way to beat a Doug Flutie team is to have him watching from the sideline. And we were a team that could put together long drives.”

Flutie would win the CFL’s Most Outstanding Player Award in 1996 and 1997, but in 1995 he was clearly a compromised quarterback from his elbow surgery. Still, an 80 percent Flutie was better than most any playcaller, so the Stallions’ defense, led by Payton, Matt Goodwin, O.J. Brigance and Jearld Baylis, pressured Flutie at every opportunity. Tracy Ham (213 passing yards) and Mike Pringle (137 rushing yards) kept the Stampeders defense on the field as much as possible, and Baltimore’s special teams carried the day. Punt returner Chris Wright, who had three returns for touchdowns in the regular season, started the scoring with an 84-yard run back for a score just 2:12 into the game; Brigance’s blocked punt in the second quarter resulted in another special teams touchdown.

“I saw their heads go down and I just kind of remember that moment as a turning point,” Huerta remembers of Brigance’s block. “In a football game, inevitably, the winning team is always going to need some good plays, and they had their share, but I just remember our team would forget about it if Calgary had a good play. We would just try to top them, and it seemed like we broke their spirit.”

Huerta, kicking with the wind in the second and fourth quarters, knocked through five field goals, including a 53-yarder that still stands as the longest field goal in Grey Cup history.

“I was such a fan of Doug Flutie in high school, I hated that he lost the game, but I’m so glad we won,” he says. “One of the best moments of my athletic career, if not the best.”

The only second-half scoring Calgary could muster was a 1-yard touchdown run from Flutie, and Baltimore won the Grey Cup in a laugher, 37-20. Ham was named MVP, but it could’ve been any number of Stallions. Baltimore was so deeply talented but it had required a complete team effort to pull off the historic win. The 1995 Stallions remain, to this day, the first team in CFL history to win 18 games.

“With regards to that Grey Cup, and the style in which we lost in ’94, with the field goal and some questionable calls, we took that to heart the next year and it was like unfinished business,” Pringle says, adding that the phrase was engraved into their Grey Cup rings. “We celebrated that night and we had the whole province to ourselves. We closed down the whole country.”

A Grey Cup win for a Canadian franchise could bring out hundreds of thousands of fans for a downtown parade. There was no parade in Baltimore. The NFL was already coming to town, and the Stallions became an immediate afterthought. (Speros did sponsor a 20-year reunion this past summer that included many former players.)

And with the Ravens (née Browns) headed east for the 1996 NFL season and beyond, the only question was what would ultimately happen to the Stallions.

A few months later, the CFL quashed the entire American expansion effort, folding the teams in Birmingham, Shreveport, Memphis and San Antonio, and moving the Baltimore franchise to Montreal. Just as the Stallions had returned football to Baltimore after a 10-year wait, they would now bring football back to Montreal nine years after the Alouettes folded before the 1987 season. Jim Popp, who was the general manager of the Baltimore Stallions, remained with the Alouettes where he won three more Grey Cups and is still the team’s GM and head coach. In 1997, Larry Smith resigned as CFL commissioner and became president and CEO of those same Alouettes.

Officially, the Montreal Alouettes do not recognize the Stallions’ two-year-existence as part of their official team history.

To this day, the Stallions’ victory remains an odd footnote in CFL lore. Perhaps if the team had survived to establish a more well-known identity, it wouldn’t seem so out of place, but knowing that the CFL is likely never to expand into the U.S. again means it now lives in its own singular bubble for all time.

And even though it resulted in the successful return of football to Montreal – a public relations coup for the league that probably can’t be overstated – and the eventual retraction of the CFL to a purely Canadian endeavor, the idea of an American team in possession of the Grey Cup is still a lamentable fact of history for some.

“I’m sure for some people it was enraging,” Cosentino says. “I felt like it was the right moment for that to happen, but I knew this was going to be a problem for a lot of CFL fans. I did not expect the league to contract so quickly. So in hindsight, I can tell you I hate that moment, today, knowing that the league stayed and those teams folded, but at the time, I remember being OK with it after witnessing the year they had.

“They deserved to win, but yeah, if you’re just talking about that question: How do you feel as a Canadian with the Grey Cup sitting in Baltimore? I think I hate it. I think it’d be something we’d want back real fast.”

For Mike Pringle, who played nine more seasons, appeared in two more Grey Cups and was elected to the Canadian Football Hall of Fame in 2008 in his first year of eligibility, that frigid day in Regina remains a point of pride that can never be taken away, even if the Stallions never properly received their due.

“It will be stamped into history because nobody can trump that,” he says. “But we were such a strong team offensively, defensively, and in special teams. We had so much talent on that team. We could’ve competed with anybody.

“I think it was probably the best team in the history of the CFL, bar none.”

Link to original article in Rolling Stone magazine.