Wild Stallions – How a Team From Baltimore Rocked the Canadian Football League Forever

Finally, on November 6, 1995, two days after the Stallions defeated the Winnipeg Blue Bombers, 36-21, in the first round of the CFL playoffs, the news was made official. The Browns were moving to Baltimore for the 1996 season, which meant the Stallions – by virtue of their own popularity, which proved that professional football in the city was a viable enterprise – were effectively gone. In the New York Times’ 1,200-word story about Modell the next day, the Stallions were not mentioned even once.

“When we found out it was a fait accompli,” Pringle says, “I took the Browns’ roster and I wrote their names on tape and put them over everybody’s nameplate in the locker room – except mine.”

Pringle’s motivating maneuver added some levity to a stressful situation, but Huerta’s seven field goals in the South Division final ensured that Baltimore would survive to play one final game in franchise history – in Regina for the Grey Cup.

The start of the game was delayed on account of the unyielding winds, and there was doubt that temporary seating at one end of the stadium would even stay up in such conditions. There was snow on the sidelines but the sky was clear and the wind biting. The Stallions had practiced that week in Regina so the weather was not a shock to their system. In fact, they planned to use the elements to their advantage by running the ball, milking the clock, and tiring the Calgary defense.

“We were going to stay on the field offensively as long as we could – and keep Doug on the sideline,” Pringle says. “The best way to beat a Doug Flutie team is to have him watching from the sideline. And we were a team that could put together long drives.”

Flutie would win the CFL’s Most Outstanding Player Award in 1996 and 1997, but in 1995 he was clearly a compromised quarterback from his elbow surgery. Still, an 80 percent Flutie was better than most any playcaller, so the Stallions’ defense, led by Payton, Matt Goodwin, O.J. Brigance and Jearld Baylis, pressured Flutie at every opportunity. Tracy Ham (213 passing yards) and Mike Pringle (137 rushing yards) kept the Stampeders defense on the field as much as possible, and Baltimore’s special teams carried the day. Punt returner Chris Wright, who had three returns for touchdowns in the regular season, started the scoring with an 84-yard run back for a score just 2:12 into the game; Brigance’s blocked punt in the second quarter resulted in another special teams touchdown.

“I saw their heads go down and I just kind of remember that moment as a turning point,” Huerta remembers of Brigance’s block. “In a football game, inevitably, the winning team is always going to need some good plays, and they had their share, but I just remember our team would forget about it if Calgary had a good play. We would just try to top them, and it seemed like we broke their spirit.”

Huerta, kicking with the wind in the second and fourth quarters, knocked through five field goals, including a 53-yarder that still stands as the longest field goal in Grey Cup history.

“I was such a fan of Doug Flutie in high school, I hated that he lost the game, but I’m so glad we won,” he says. “One of the best moments of my athletic career, if not the best.”

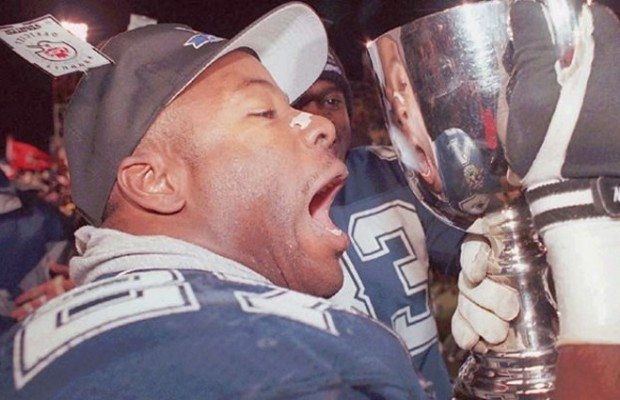

The only second-half scoring Calgary could muster was a 1-yard touchdown run from Flutie, and Baltimore won the Grey Cup in a laugher, 37-20. Ham was named MVP, but it could’ve been any number of Stallions. Baltimore was so deeply talented but it had required a complete team effort to pull off the historic win. The 1995 Stallions remain, to this day, the first team in CFL history to win 18 games.

“With regards to that Grey Cup, and the style in which we lost in ’94, with the field goal and some questionable calls, we took that to heart the next year and it was like unfinished business,” Pringle says, adding that the phrase was engraved into their Grey Cup rings. “We celebrated that night and we had the whole province to ourselves. We closed down the whole country.”