Wild Stallions – How a Team From Baltimore Rocked the Canadian Football League Forever

With the 1994 baseball strike underway, the Baltimore CFLs, as they were known, were the only major professional sports team playing in the city at that time. Not only did Speros use that to his advantage in promoting the team, he reaped the benefits of ad dollars that were no longer earmarked for the Orioles and had to go somewhere.

“You never like to benefit from someone else’s misfortunes,” CFL commissioner Larry Smith said at the time, “[but] the strike is not going to do anything but help us.”

And Baltimore rewarded its fans with a surprise run to the Grey Cup, and that was a wakeup call to Canadian fans. Much in the same way that NFL rosters are often very American, CFL rosters are actually very Canadian. There’s this perception that it’s all just NCAA cast-offs and players who maybe can’t cut it in the NFL. But the reality is that these rosters are consciously Canadian, stocked with players who were born in Canada and played their college ball there. The 1995 Stallions, on the other hand, did not have a single Canadian on their roster. Smith had willfully constructed the league as United States vs. Canada, and the Stallions were the living embodiment of that ideal.

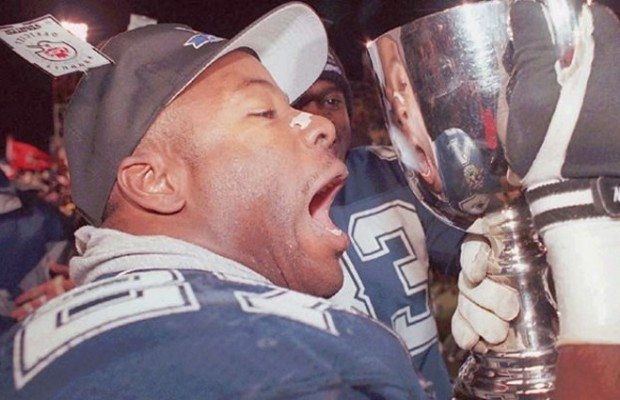

No matter their collective nationality, the Stallions were a football force that could not be stopped. They won 15 games and the roster was stocked with talent on both sides of the ball. With Pringle at running back, fellow future CFL Hall of Famer Tracy Ham at quarterback, and an offensive line that dominated at will, the offense was quick and explosive when needed. The defense, led by 18 sacks from future Hall of Fame defensive tackle Elfrid Payton (whose son is the starting point guard for the Orlando Magic), the Stallions gave up the third-fewest points in the league. On special teams, Carlos Huerta was dominant. His 57 field goals that season are still the second-most in CFL history, and in the semifinal game against the San Antonio Texans, Huerta nailed seven field goals in a 21-11 win. (He still has the gold Bulova watch he got for earning Player of the Game honors that day.) Baltimore had wanted to make him the highest-paid kicker in CFL history before the season, but Huerta chose to play out his option year in the hopes of a bigger eventual payday or even a legit shot at a starting NFL job.

A notable performance in the 1995 Grey Cup would all but assure that gamble paid off.

As a media relations director for the Toronto Argonauts, Mike Cosentino was also on the sidelines during the 1994 Grey Cup, like Huerta and many others. Even though the Argos hadn’t qualified for the championship game, all the team P.R. directors show up to work the event, which means Cosentino was among some 55,000 fellow Canadians, holding his breath that B.C. could somehow pull off the win and keep the Grey Cup within its home borders.

“It was going to be an unbelievable, ‘are-you-kidding-me?’ moment,” Cosentino says. “There was a big sigh of relief that it didn’t happen, honestly.”

But soon enough it became clear that Baltimore was back for more in ’95, that the Stallions were the class of the CFL and had a legit chance of winning it all. And among all the American CFL franchises, the Stallions were regarded internally as the only one pulling its weight at the turnstiles. As they kept winning, the fans kept showing up. The Stallions had fewer than 27,000 in attendance in a home game only once that season and typically hovered around 30,000. By the time Baltimore finished its regular season 15-3, the rumors that Art Modell was thinking of relocating the Cleveland Browns were full-blown.