Wild Stallions – How a Team From Baltimore Rocked the Canadian Football League Forever

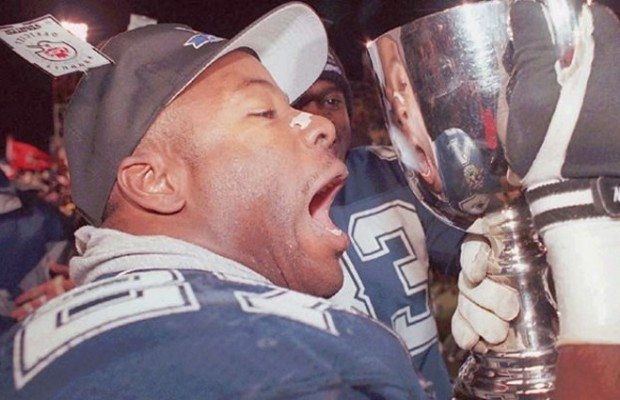

Mike Pringle holds the Grey Cup in Regina, Canada on November 19th, 1995 Tom Hanson/AP

Twenty years ago, a group of American players won the Grey Cup, broke the heart of a nation and helped bring the NFL back to Baltimore

On November 19, 1995, more than 52,000 people trudged into Taylor Field in Regina, Saskatchewan, to witness what would become the most pivotal game in the history of the Canadian Football League. It was the day of the 83rd Grey Cup, so named for the silver trophy bestowed upon the CFL’s annual champion.

The weather was very Canadian, with temperatures dipping below zero and winds gusting to around 50 mph. The crowd, though, was spirited, ready for anything and decidedly on the side of the Calgary Stampeders, led by superstar quarterback Doug Flutie. The former Boston College star had been named the CFL’s Most Outstanding Player for four years running, but 1995 was arguably his most incredible season yet. Surgery in August on a torn tendon in his throwing elbow was supposed to keep him out eight months, but he returned in time for Calgary’s regular-season finale and led them through the playoffs and to the championship game. With backup quarterback Jeff Garcia keeping the team afloat and competitive in Flutie’s absence, Calgary had gone 15-3, tied with their Grey Cup opponent for the best record in the league.

That team was the Baltimore Stallions, a franchise in only its second year of existence. (The Stampeders date back to 1935, older than all but eight NFL teams.) Under the guidance of CFL Commissioner Larry Smith – himself a former CFL player for nine seasons in Montreal – Canadian football officially entered the American market in 1993 with the Sacramento Gold Miners, excavated from the remains of the Sacramento Surge of the defunct World League of American Football. In 1994, the CFL added franchises in Las Vegas; Shreveport, Louisiana; and Baltimore. But in 1995, Smith orchestrated a radical expansion project that essentially split the CFL conferences into direct, opposing entities: the North Division with eight Canadian teams and the South Division with five American teams. CFL franchises were awarded to Memphis and Birmingham, Alabama, and the Sacramento team moved to San Antonio to play in the Alamodome as the newly christened Texans.

It was a risky power play for a league whose future was seen as somewhat tenuous, but Smith put on a brave face in public.

“I think we’ve positioned ourselves to protect ourselves,” he told TSN in an interview before the 1995 season. “Let’s face it: The NFL is very strong. We’re selling a unique product. We’re creating our own niche. We don’t compete against the National Football League. We have to compete against ourselves.”

And now, a controversial season had come down to one night in Regina. With a longer and richer history than its American counterpart, the CFL has an importance to Canadians that can’t possibly be overstated. It’s football but a slightly different blend. There are 12 players aside (not 11). You get three downs to gain ten yards (not four). The field is longer and wider, the goalposts are positioned differently, the scoring is slightly more inventive, and the game ends not with zeros on the clock but with a final play. The Stallions had already learned about this last difference all too painfully. As a nameless team adorned with a horsehead on its helmet – the NFL sued to keep them from dubbing themselves the “Colts” – the Baltimore team made it all the way to the 1994 Grey Cup and lost to the B.C. Lions, 26-23, on a field goal with no time remaining. They left the Lions’ home stadium in Vancouver disappointed but determined to return.

On the sidelines during that game was Carlos Huerta, who had been named the CFL’s West Division Rookie of the Year as a kicker for the Las Vegas Posse. Huerta was a native of South Florida, was an All-American at Miami and won a national championship with the Hurricanes in 1991. Going from The U to the uppermost reaches of professional football was an easy-enough transition for Huerta, who watched in awe as B.C.’s Lui Passaglia punched through a 38-yard kick to win the Grey Cup. As the Lions players stormed the turf in celebration, Huerta turned to his girlfriend Christine (now his wife) and smiled.

“I was born to make that kick,” he said.