The call finally came.

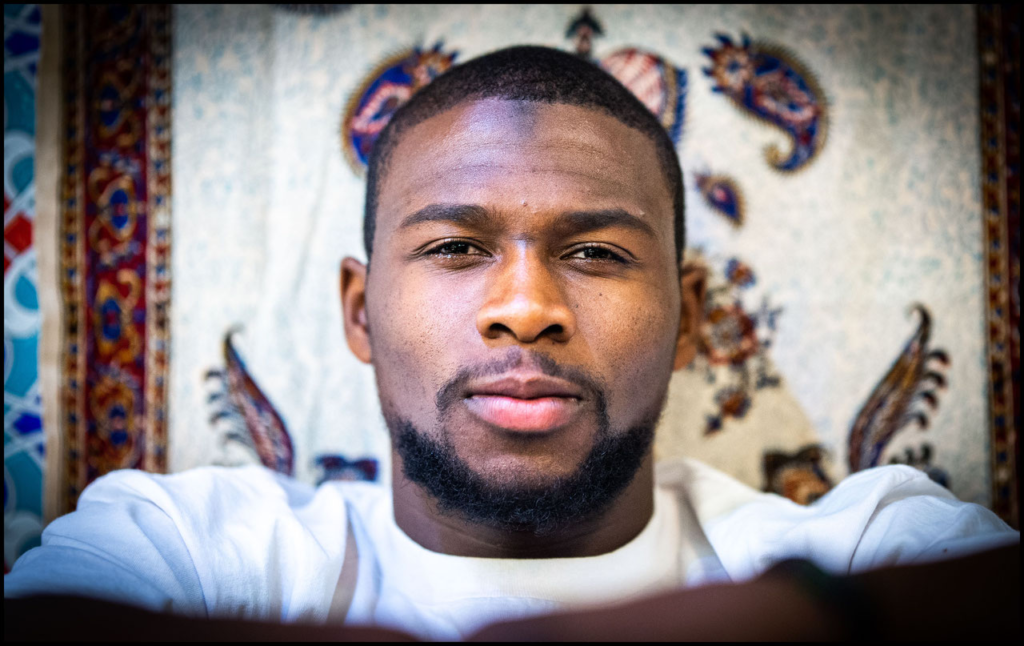

After all that time Al-Rilwan Adeyemi had spent keeping in shape over the two years since finishing college, never giving up on his dream, an NFL team was finally on the line at last.

Yet here he was, getting a rare second chance.

Sorry, he told them. Thanks but no thanks.

“When I got out here in August [of 2013], the Lions called and said someone had gone down in camp,” Adeyemi said “Obviously they wanted me to come work out for them and see if I was in shape.

“I thought about it. But for me, religion plays a big part in my life. For me, when you give your word as a Muslim, you can’t go back on it. So I couldn’t break that verbal promise that I gave Fujitsu that I was going to commit to them for that six months that I was here.”

Those six months have now stretched to six years and counting. The positive effects that Adeyemi has had on Fujitsu, and by extension the XLeague in general, cannot be denied or underestimated.

On the field, he has been the premier cornerback in the league, making the All XLeague team all six years he has been here, while helping Fujitsu reach the Japan X Bowl every year. On four of those six occasions he walked off the field at Tokyo Dome a champion, including the past three in a row.

According to XLeague statistics, Adeyemi has 17 regular-season career interceptions, two of which were returned for touchdowns. He has either shared, or was outright league leader in INTs four times. An argument could be made that would have many more, but teams understandably tend not to throw his way. Last year, Adeyemi had a career-high five interceptions, including one he took back 99 yards for a score.

“He got over here more or less the same time that I did,” says IBM Big Blue quarterback / head coach Kevin Craft, whose team has lost twice to Fujitsu in the Japan X Bowl. “On the field for them, obviously he’s a good player.

“But what I hear more than anything about Ade is more about him off the field. He’s genuinely a nice person, he’s nice to be around, he always has kind words, he’s always trying to help people.”

“He’s the type of person that you want to have on your team. He’s the type of person that you want to have in your country. He probably fits in every well to Japan, the culture.”

“It’s been huge, having a guy like him around. He’s just a good guy, a good dude. He’s been here for so long, he’s engulfed in the Japanese culture. He knows the language well, so he’s been able to teach us things about the language, about the culture in general. Things you should do, shouldn’t do.

“That’s something that he told us might have taken for us years to learn. It took him five, six years to learn, so you would expect the same. So having him around has been a true blessing.”

“They decided to leave me in Nigeria for basically the first 10 years of my life,” he says. “My mother left when I was 4. I grew up basically with aunts, uncles and grandparents for the first 10 years of my life, because they wanted me to grow up with more humble beginnings then they thought that American kids would grow up with.”

“Imagine National Geographic, living under a dollar a day,” he says of the rural life. In Lagos, his relatives were educators and politicians, and he got to live the high life, attending private and military schools. “I got the best of both worlds.”

“We’d go into rundown villages and take off the roof and use it as tennis rackets,” he says. “We would take a tennis ball and take a cup and wrap gold tin foil around it, and that would be our World Cup trophy. On weekend, we would set up tournaments with the neighborhood kids, and whoever won that got to keep it for the week.”

“There were some kids that were amazing, and then there were some kids that were ignorant,” he says. “Kids are very truthful. They would ask questions like, ‘Did you live in a hut?’ Things they see on TV. ‘Did you guys wear clothes?’ They were so curious. But you couldn’t hold it against the kids. Part of that was educating the kids.

“But for me, I come from an athletic background, so making a friend was as simple as, can I play. Soon it was, ‘Yeah you can play,’ and, ‘Oh, he’s good – we’re friends.'”

At Santa Monica High School, Adeyemi focused mainly on football and track and field, running the 100 meters in 10.8 seconds. Because of his speed, he was even recruited for the baseball team, whose coach was also a coach on the football team. “Come steal some bases for me,” he would plead to no avail.

Because of the defensive system the school used, Adeyemi played safety, resulting in “a lot of interceptions.” An All-Ocean League selection, he still clearly recalls the eight picks he had his senior year, and the four that he dropped. That earned him a full-ride to USD, a Division I-AA school where he was switched to cornerback and became a starter from day one.

He left San Diego tied for the school record for career interceptions with 15. In his senior year in 2011, Adeyemi helped lead the Toreros to a long-awaited Pioneer Football League championship, and was named to the all-league first team for the second straight season. In 2008, he had been the league’s Freshman Player of the Year on defense.

“I finished school in 3 1/2 years, that way I could have that spring to train and get ready for the next level, wherever that may be,” he says.

But he also got a first-hand look at how the odds would never be in his favor.

“I had a pretty good college career, if you put things in perspective. But coming from a small school and being 5’9” [175cm, although he is listed at 178cm], sometimes you get overlooked. And I came out in a very competitive year, 2011-2012. So that year, obviously I wasn’t drafted.

“I went to a couple of tryouts. I went to the Giants, and they had like eight corners on the roster, something silly, and that was coming off their Super Bowl year. I was just a body.”

Thom Kaumeyer, who spent three years as an assistant coach at Fujitsu before becoming IBM’s defensive coordinator last season, knows what it takes to make the NFL. He played five seasons with the Giants and Seattle Seahawks.

“Sometimes it’s nothing about lacking,” Kaumeyer says. “When you start talking about the NFL, it’s elite. And guys that are taller have a little bit more range to do things and make mistakes. When you’re 6-foot, 5-11, you have to do everything right.”

“I test pretty well,” he says. “Testing is about preparation. I prepared decently. I had good coaches who helped me prepare well. So I tested pretty well and I had another opportunity that next year with the Lions.”

“They were like, yeah, it’s a numbers game. They kind of give you the same runaround, and I was like, all right, I understand. ‘Well, we’ll call you if someone gets hurt.’ I just went a whole year without anyone calling me. And then the whole Japanese opportunity [came up].”

“We were looking for DBs at that time and we called Brad Brennan, and finally he got him,” said former Frontiers head coach Satoshi Fujita, the architect of the Fujitsu’s championship run and now the team’s senior advisor. “We asked Brad to send him one time to Japan. And we met him, and we really liked him. And he really liked it here.”

Having turned down the Lions, Adeyemi was impressed with what he saw with the Frontiers and the league in general, even though an unexpected off-field incident kept him out of the early part of his first season.

“I thought they had decent talent,” Adeyemi said of the Frontiers, who at that point had been to the Japan X Bowl in three of the previous six years, but had lost each time and had yet to win a championship. “I thought we were missing a couple of things, but I thought we could really compete.”

“Luckily for me, I didn’t play the first half of that season, so I didn’t play against the teams that weren’t as good,” he added, referring to the fact that under the format at the time, the top teams would play weak teams in their division early in the schedule.

“I carry the sickle cell trait, and after a certain elevation, my blood starts to thin,” he explains. “My blood starts to lose white blood cells after a certain altitude, and I wasn’t aware of that. I got really sick, and then my spleen was affected, and I was hospitalized for a few days.”

One constant during the dynastic reign has been Adeyemi, who has been the foundation on which the defense is built. He has become that not only with intensity he displays on every play, but also a desire to help his teammates reach their full potential.

To do that properly – that takes the right attitude of seeing the Japanese players not as inferior, but as fellow athletes striving to learn, says Kaumeyer.

“I think the best thing about Ade was when he came here…he understood about Japanese football,” Kaumeyer says. “That for him, it gave him a chance to be able to do what he wants to do and enjoy football, but also teach Japanese players how to do different techniques.

“Sometimes guys come over here and they think they know everything because they’re from America and Japanese players don’t. That’s a fallacy. Japanese players study, they know techniques. Sometimes it’s just the grey areas that they got to learn. And Ade did a phenomenal job of being able to show our players the difference between making a play and being aggressive, as opposed to just making a tackle.”

“The political landscape definitely doesn’t make it easy being Muslim in the States,” he says. “But part of being American is being different. At a certain time, the Jews went through those same persecutions. The Irish went through those same persecutions. Right now, the Hispanics are going through same persecutions in terms of immigrant bodies coming into the United States.

“But there are a lot of people who are doing great things in the communities that are partnering with their Muslim neighbors and bringing some of the positive news to light. Usually immigrants, when they come to a foreign country, they’re hungry. They want to grind. That’s why you see a highly educated population in the immigrant communities.”

Coming to Japan, Adeyemi says he has faced none of the animosity found back home. Like the California kids curious about the new Nigerian boy on the block, he finds the Japanese open to learning about an unknown culture.

“It’s like being anywhere else,” he says. “There’s no hindrance. The Japanese were very curious. There’s a mosque basically everywhere you look. There are that many, but people don’t know about them. For Islam, you can pray anywhere. Just find your little space and say your prayers. God is everywhere.

“Japanese humility, kindness and respect, which are all tenets that the Quran teaches us to practice, makes it easy to practice Islam in Japan.”

Differences in religion have not caused any problems with his American teammates; in fact, it has enhanced the bond.

“We talk about it all the time,” says Birdsong, a Virginia native who attended three colleges in the U.S. South. “He took me to my first mosque. I grew up Catholic, and you’re not supposed to like each other. But we get along great. We’re very open, and we talk about everything. We have no problem with it. I like learning.”