By Paul Newberry

For years, Sue Ferrara has followed the same routine on Super Bowl Sunday.

And, no, it has nothing to do with the big game.

About the time the Philadelphia Eagles and Kansas City Chiefs kick it off for the NFL championship, Ferrara will head to her two favorite grocery stores, reveling in aisles and checkout lines that are more wide open than a wide receiver after busted coverage.

“I’m sure it will be a very, very well-watched game where I live,” said Ferrara, whose home in Princeton, New Jersey is pretty much the dividing line between those who root for the Eagles and those who back the New York Giants. “Which means when I got to Trader Joe’s, there will be no one there. When I go to Wegmans, there will be no one there.”

Get this: There are tens of millions of Americans who couldn’t care less about the Super Bowl.

People have their photo taken with signage for the Kansas City Chiefs NFL football team while visiting a display Thursday, Feb. 9, 2023, at Union Station in Kansas City, Mo. (AP Photo/Charlie Riedel)

Count Ferrara, a freelance writer and school board member, among them.

“I never connected with football,” she said. “Then they started doing studies on CTE and the brain damage that can be done. I think football is past its prime, quite honestly.”

Try telling that to all those folks who will be throwing elaborate parties and wagering billions of dollars on the outcome of a game that has become our unofficial national holiday.

The Super Bowl is essentially the last major event that can unite so many Americans in a common purpose: sitting in front of a TV all day, washing down wings and nachos with plenty of ice cold beer, lamenting how they just lost 50 bucks because the coin toss was tails instead of heads.

An order of “boneless chicken wings” is shown at a restaurant in Willow Grove, Pa., Wednesday, Feb. 8, 2023. With the Super Bowl at hand, behold the cheerful untruth that has been perpetrated upon (and generally with the blessing of) the chicken-consuming citizens of the United States on menus across the land: a “boneless wing” that isn’t a wing at all. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

The official viewing audience — which came in at more than 112 million a year ago — dwarfs anything else in our increasingly fragmented media landscape.

A survey commissioned in part by the NFL claims 208 million-plus tuned in for at least some portion of last season’s extravaganza, perhaps just to watch the halftime show and/or commercials.

But even if you take the NFL’s word for it, that means more than 100 million Americans didn’t watch at all.

People like Deepak Sarma, a professor at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland who also serves as a cultural consultant for television shows and streaming networks.

Until he went to the gym the other day, he didn’t even realize Super Bowl Sunday was this Sunday.

“I go to my locker and two guys I know are sitting around talking about some players and quarterbacks,” Sarma said, chuckling. “Now, I don’t know the names of any of these things. I look at them like, ‘Ohhh, did someone say the Chiefs? Hey, are you talking about the Super Bowl?’ And they’re like, ‘Yeah, you big dummy.’

“So I said to them, ‘Who’s in it?’ And they said the Kansas City Chiefs and, uhh, the Philadelphia Eagles, I believe. They kept on going and I said, ‘When is it?’ And they were like, ‘Dude, it’s this weekend.’ It was really funny. I had no clue because it’s not interesting to me.”

Kansas City Chiefs quarterback Patrick Mahomes (15) pauses on the field with tight end Jody Fortson (88) during an NFL football practice in Tempe, Ariz., Thursday, Feb. 9, 2023. (AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin)

Many of Sarma’s students apparently feel the same way.

When he assigned two papers that are due on Monday — again, before he even realized what was happening the day before — no one in the class objected.

“These kids will not be watching the game,” Sarma said.

Neither will Alonso Duralde, a Los Angeles-based film critic. He and his husband don’t have any special plans for Super Bowl Sunday, and they’re hardly alone in Southern California.

“We used to live in Dallas,” he said. “Super Bowl Sunday was a great day to go to the movies. You could count on it being pretty empty. In California, not so much. There’s a lot of people who watch the game, but a lot of people who don’t. People act like the streets are empty during the Super Bowl, but that doesn’t really happen here.”

Putting on his academic cap, Sarma wonders why sports — and the Super Bowl, in particular — has such an effect on American society.

“It brings communities together in a really artificial way,” he said. “Do we need this? Why do we need this? They are great distractions when there’s so many more important things going on.”

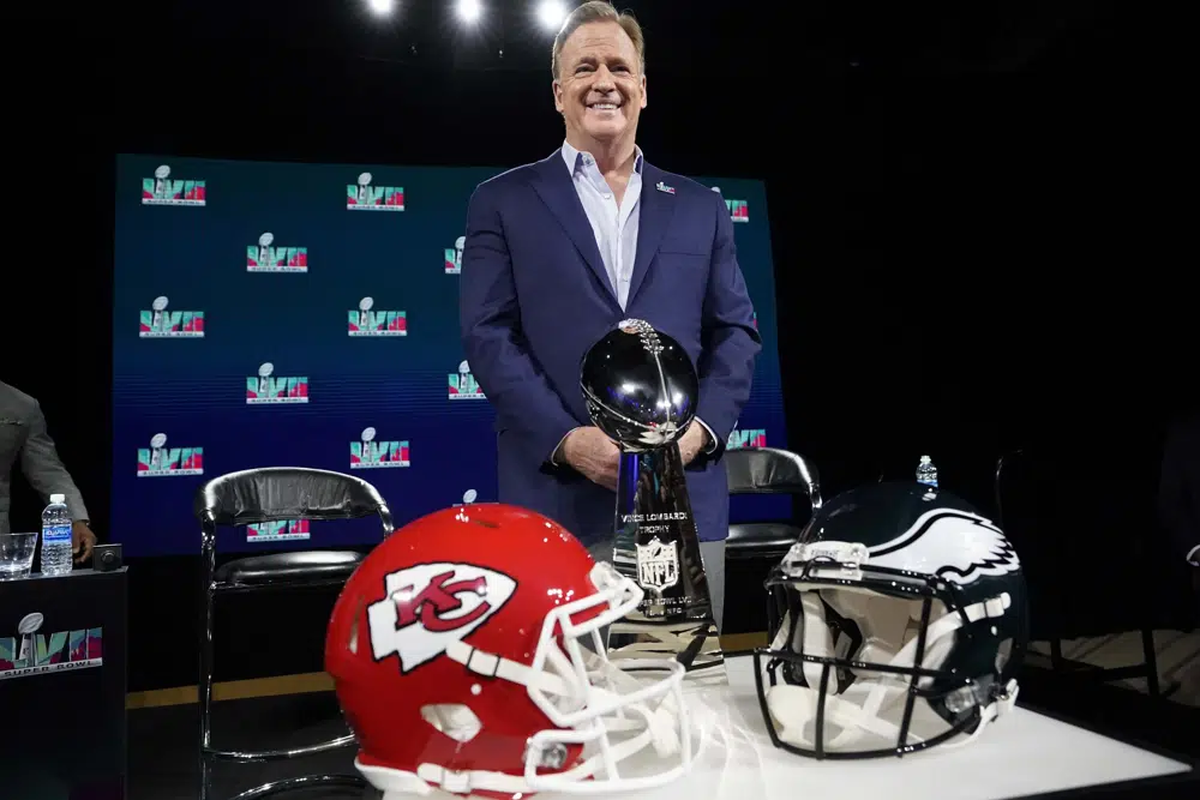

From a more practical standpoint, this Sunday provides the rarest of opportunities for those who aren’t worshipping at the Church of Goodell. (For those non-believers, Roger Goodell is commissioner of the NFL.)

“We get to enjoy empty restaurants, empty gyms,” Sarma said, a hint of glee in his voice. “In a way, we get to reclaim our country. It’s become kind of a meditative space apart from it all. We’re not going to get sucked into it.”

It’s becoming easier and easier to avoid the Super Bowl hype.

With so many networks and streaming services, there are countless counter-viewing options for those who don’t wish to watch a football game Sunday evening.

Come Monday morning, far fewer people will feel left out around the water cooler because so many are now working from home. (Do they even have water coolers anymore?)

The Philadelphia Eagles work out during an NFL football Super Bowl team practice, Thursday, Feb. 9, 2023, in Tempe, Ariz. The Eagles will face the Kansas City Chiefs in Super Bowl 57 Sunday. (AP Photo/Matt York)

Even before the pandemic changed our work habits, Duralde found it was much easier to connect with those who didn’t want to talk about zone coverages and point spreads.

“Like anything, the internet has its good and bad sides,” he said. “But people are able to find other people who share the exact same interests as they do, whatever that is.

“The virtual water cooler is wherever you want to find it.”

For those who tune out the game, there are some drawbacks to Super Bowl Sunday.

For instance, when Ferrara is perusing the shelves at Trader Joe’s and Wegmans, she probably won’t find everything on her list.

“Will there be any food left? Who knows?” she quipped. “We could be eating the remains of the sushi no one wanted. Or the last sandwich that has something funky on it, like brie.”

Duralde is planning a low-key day, like so many of his fellow Americans who won’t be watching the Super Bowl.

“There was a time when we would plan alternative events,” he said. “Ahh, yes, this is the day we go to the movies, or this is a day we go shopping.”

Then Duralde uttered the words that many will consider heresy, but just as many view as gospel.

“It’s just,” he said, “another Sunday.”